The link between alcohol and cancer has been established by medical professionals since the 1980s. But public awareness of that link is low.

A bill pending in the Alaska Legislature aims to change that.

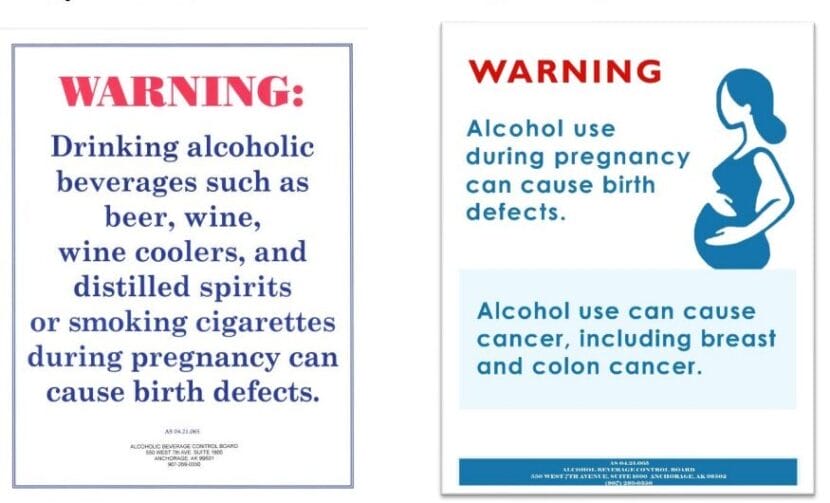

The measure, House Bill 298, would require businesses that sell alcoholic beverages post signs warning of the cancer link. The cancer message, as proposed by the bill, would augment the currently required message warning that consumption of alcohol during pregnancy can cause birth defects.

The bill has no sponsors from the Republican-dominated House majority, and there is no Senate version. The prime sponsor, Rep. Andrew Gray, D-Anchorage, said he had minimal expectations about its fate when he introduced it in January. “When we filed it, we expected to not get a hearing at all,” he said. To at least raise awareness about the alcohol-cancer link, he said, he issued a press release.

Then, as he describes it, something surprising happened: The bill started to move. “Lo and behold, we got a hearing,” Gray said. It got another hearing and advanced from the House Health and Social Services Committee to the House Labor and Commerce Committee.

Gray and his aide David Song discussed the public-awareness gap during a hearing on Monday in the second committee.

“Alcohol-related cancers affect tens of thousands of Americans each year. Despite the longstanding medical fact that alcohol increases cancer risk, there has not been an accompanying change in public perception about the risks associated with alcohol consumption,” Gray told the committee.

A 2020 survey by the National Institutes of Health found that 10% of respondents believed that wine drinking lowers cancer risks, which is false, Song told the committee. The cancer link for beer, wine and liquor consumption was acknowledged by only 24.9%, 20.3% and 31.2% of survey respondents respectively, he said. In contrast, about 90% of Americans say tobacco use causes cancer, a message imparted in warning labels required on tobacco products, he said.

“So, in other words, the warning labels that connect a product with cancer do work in terms of increasing public awareness,” Song said.

Along with tobacco use and obesity, alcohol use is one of the main cancer risk factors over which people have some control. The American Cancer Society links alcohol use to numerous types of cancer.

A recent study published in the medical journal The Lancet that evaluated global cancer statistics ranked alcohol use as the No. 2 modifiable cancer risk.

Warning signs about the alcohol-cancer link are required in a few places. One is the Yukon Territory in Canada, Thomas Gremillion, director of food policy at the Consumer Federation of America, told the committee. His organization favors a national rule requiring such signs as well as state efforts such as this bill, he said.

But there is also skepticism about the idea.

House Majority Leader Dan Saddler, R-Eagle River, at a House Health and Social Services Committee hearing on March 12, said he has philosophical problems with the bill.

“The question that comes to my mind is: How much obligation does the state have to inform people of the risks of legal activities?” Saddler said.

The same arguments about alcohol’s cancer-related risk warnings could be made for injury-warning signs on bikes, cars, private airplanes or roller skates, Saddler said, presenting questions about whether there is a threshold for such warning requirements.

“They are good-intentioned. But the road to, say, a ‘cotton-wool’ state could be paved with good intentions,” he said, using a term for bandages used over-protectively.

Gray said a constituent of his, a breast cancer survivor, brought up another concern: Although only a light drinker, he said, she worried that she and others might be blamed for bringing their cancers on themselves.

Those objections notwithstanding, Gray said the bill might attract support from majority members. “I think there’s a chance that we could get it to the floor,” he said. If not, its substance could be added to a different bill, he said.

An amendment passed in the House Health and Social Services Committee that seemed to simplify the measure may have created a hurdle, however. The amendment changed the on-site requirement from three signs, as currently is in law, to two. Instead of requiring two separate signs warning against minors’ unlawful entry and use of alcohol, the bill as amended would combine warnings about minors into a single sign.

Replacing just one set of signs – the point-of-sale warning about health effects — would have cost under $10,000, too little to warrant a fiscal note describing costs to the state, Gray said. But replacing two types of signs, along with the need to mail new signs to remote sites, brings the estimated cost to around $25,000, Joan Wilson, executive director of the Alaska Alcohol and Marijuana Control Office, said at Monday’s hearing.

That is enough to justify a fiscal note and, according to legislative rules, consideration by the House Finance Committee, Gray said.

“If I wanted this to go to the floor, I’d want to avoid Finance, which means I’d want a zero fiscal note,” he said.

This story originally appeared in the Alaska Beacon and is republished here with permission.