For the first time, tiny bits of plastic have been found in body tissue of Pacific walruses, lodged in the animals’ muscles, blubber and livers.

The findings, from a University of Alaska Fairbanks student research project, add to growing knowledge about the widespread presence of microplastics in the world’s natural environment, even in remote locations.

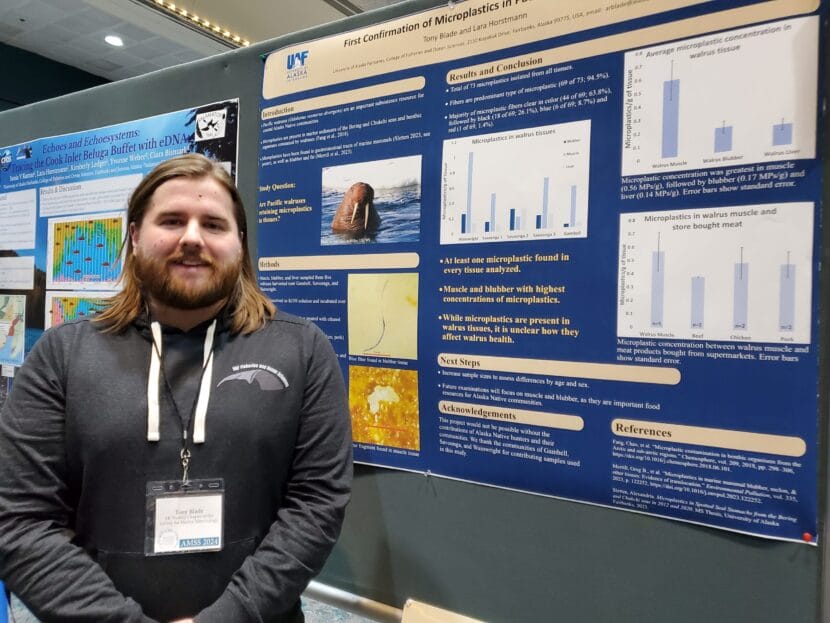

“It’s a reflection of the plastic age we live in. It’s ubiquitous,” said Tony Blade, a UAF undergraduate who presented his findings in a presentation at last week’s Alaska Marine Science Symposium, a major science conference held annually in Anchorage.

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic, smaller than 5 millimeters – or one-fifth of an inch – in length, with some too small to be seen without microscopes.

Blade’s project, conducted under the supervision of UAF marine biology professor Lara Horstmann, examined body tissues of five walruses harvested by subsistence hunters. The samples were donated by hunters from Gambell and Savoonga, Siberian Yup’ik villages on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Strait region, and from Wainwright, an Inupiat village on the Alaska mainland.

Every one of the 15 samples – muscle, fat and liver from each of the five walruses — held microplastics.

In all, there were 73 microplastics isolated from the tissues, almost all of them fibers. In four of the walruses, muscle tissue had the highest concentration of microplastics, though in one walrus from Savoonga, blubber had the highest concentration. Most of those found were clear; black fibers were the second-most prevalent.

Blade’s research shows that the plastic bits, far too small to be seen with the naked eye, are somehow getting beyond stomachs and digestive tracts and lodging directly into body tissues – a process that scientists call translocation. Although his work is the first to make such a finding in Pacific walruses, emerging research elsewhere is turning up microplastics in body tissues of other marine mammals.

Exactly how the plastics are passing through biological barriers to get into tissues is yet unknown, Blade said. Also yet to be understood, he said, is what the presence of plastic in their bodies does to the walruses. “We don’t know what that means as far as biological health of the animal,” he said.

Follow-up work by Blade and Horstmann is already underway, with samples from 20 walruses harvested by St. Lawrence Island hunters. That work will examine whether there are any age- or sex-related patterns to microplastics presence in body tissues, Blade said.

One reason that walruses were chosen for his project, he said, is that they are culturally important to Indigenous people of the region.

Another important reason is the way that they eat, he said. Walruses feed on clams, snails and other creatures that dwell on the ocean floor, the area of the sea known as the benthic zone.

“They’re digging through ocean sediment. And prior studies have shown that microplastics in the Bering Strait region are settling into the sediments of that area, as well as being taken up by organisms like mussels, crustaceans, invertebrates that walruses are eating directly,” he said.

The idea that walruses are more at risk for plastic consumption because of their benthic eating habits is consistent with recent findings by another UAF researcher who has focused on microplastics ingested by spotted seals in the Bering Strait region.

Alexandria Sletten, whose project was the thesis for her newly acquired master’s degree, also presented her findings at the symposium’s poster session in a follow-up to a presentation last year.

Of the 33 seal stomachs she examined, 32 had plastic. Those seals that fed more heavily at the benthic level – where walruses eat — had more plastics in their stomachs than the seals that fed on prey at the nearer-to-the-surface area known as the pelagic level, she found.

Blade’s walrus discoveries also fit with some groundbreaking findings by Duke University researcher Greg Merrill, who recently documented the presence of microplastics in body tissues of a variety of marine mammals.

Merrill, in a presentation at the symposium, described his findings about tissues from 22 marine mammals of 12 species.

Animals tested ranged from bottleneck dolphins and whales found dead after strandings in North Carolina and California to mammals harvested by subsistence hunters or found stranded in Alaska: bearded, spotted and ringed seals and beluga, gray, minke and fin whales.

Two-thirds of the animals tested had microplastics, mostly fibers, in at least one type of body tissue, according to Merrill’s study.

“Translocation is occurring. Plastic that is ingested, those microplastic particles, are moving around in the body and depositing into different tissues,” Merrill said in his conference presentation.

The marine mammals are consuming plastics indirectly, eating prey that acquired the microplastics at lower levels in the food web, Merrill said. But even if the consumption is indirect, the quantities can be staggering, he said.

Large filter-feeding baleen whales are taking in up to 10 million plastic particles a day, “which is a pretty staggering number.” While most are expelled out in feces, some are passing through to various body parts, he said.

Merrill was able to find microplastics in preserved samples dating back to 2001, indicating that microplastics have been finding their way into marine mammal bodies for decades.

“It’s a process that has been happening for quite some time, likely since plastics have been ending up in the environment, dating back to post-World War II,” he said.

This story originally appeared in the Alaska Beacon and is republished here with permission.